What is learning? A definition and discussion. Is learning a change in behaviour or understanding? Is it a process? Mark K Smith surveys some key dimensions and ideas.

A definition for starters: Learning is a process that is often not under our control and is wrapped up with the environments we inhabit and the relationships we make. It involves encountering signals from the senses; attending to them; looking for connections and meanings; and framing them so that we may act.

contents: introduction · definition · what do people think learning is? · learning as a product · learning as a process · experience · reflective thinking · making connections · committing and acting · task-conscious or acquisition learning, and learning-conscious or formalized learning · learning theory · further reading · references · acknowledgements · how to cite this article See, also, What is education?

Over the last thirty years or so, ‘learning’ has become one of the most used words in the field of education. Adult education became lifelong learning; students became learners, teachers facilitators of learning; schools are now learning environments; and learning outcomes are carefully monitored. This learnification of the language and practice of education (Biesta 2009, 2018: 245) is in part due to the rise of individualizing neoliberal policies. Developments in learning theory have also contributed.

Yet, for all the talk of ‘learning’, there has been little questioning about what it is, and what it entails. As Jan De Hower et. al. (2013) noted, ‘questions about learning are addressed in virtually all areas of psychology. It is therefore surprising to see that researchers are rarely explicit about what they mean by the term’. There has been a similar situation in the field of education. It is almost as if ‘learning’ is something unproblematic and can be taken for granted. Get the instructional regime right, the message seems to be, and learning (as measured by tests and assessment regimes) will follow.

The reality is that learning, as Lynda Kelly (2002) put it, ‘is a very individual, complex, and, to some degree, an indescribable process: something we just do, without ever thinking too much about it’. It is also a complex social activity. Perhaps the most striking result of recent research around learning in childhood and adolescence is that very little comes through conscious and deliberate teaching (Gopnik 2016: 60). It comes from participation in life.

[O]ther kinds of social learning are more sophisticated, and more fundamental. They are evolutionarily deeper, developmentally earlier, and more pervasive than schooling. They have been much more important across a wide range of historical periods and cultural traditions.

Children learn by watching and imitating the people around them. Psychologists call this observational learning. And they learn by listening to what other people say about how the world works—what psychologists call learning from testimony. (Gopnik 2016: 89)

In this article we go back to basics – and begin by examining learning as a product and as a process. We also look at Alan Roger’s (2003) helpful discussion of task-conscious or acquisition learning, and learning-conscious or formalized learning.

From there we turn to competing learning theories – ideas about how learning may happen.

What do people think learning is?

Some years ago, Säljö (1979) carried out a simple, but very useful piece of research. He asked adult students what they understood by learning. Their responses fell into five main categories:

- Learning as a quantitative increase in knowledge. Learning is acquiring information or ‘knowing a lot’.

- Learning as memorising. Learning is storing information that can be reproduced.

- Learning as acquiring facts, skills, and methods that can be retained and used as necessary.

- Learning as making sense or abstracting meaning. Learning involves relating parts of the subject matter to each other and to the real world.

- Learning as interpreting and understanding reality in a different way. Learning involves comprehending the world by reinterpreting knowledge. (quoted in Ramsden 1992: 26)

As Paul Ramsden (1992) pointed out, we can see immediately that conceptions 4 and 5 are qualitatively different from the first three. Conceptions 1 to 3 imply a less complex view of learning. Learning is something external to the learner. It may even be something that just happens or is done to you by teachers (as in conception 1). In a way, learning becomes a bit like shopping. People go out and buy knowledge – it becomes their possession. The last two conceptions look to the ‘internal’ or personal aspect of learning. Learning is seen as something that you do to understand the real world.

In some ways, the difference here involves what Gilbert Ryle (1949, 1990) termed ‘knowing that, and ‘knowing how’. The first two categories mostly involve ‘knowing that’. As we move through the third we see that alongside ‘knowing that’ there is growing emphasis on ‘knowing how’. This system of categories is hierarchical – each higher conception implies all the rest beneath it. ‘In other words, students who conceive of learning as understanding reality are also able to see it as increasing their knowledge’ (Ramsden 1992: 27). There is also a difference between answer 1 and answers 2-5. The former has a stronger focus on learning as a learning as a thing or product. Learning is more of a noun here. The other answers look to learning only as a process.

Learning as a product

Pick up a standard psychology textbook – especially from the 1960s and 1970s and you will probably find ‘learning’ defined as a change in behaviour. Sometimes it was also defined as a permanent change. By the 1980s less crude definitions gained in popularity. For example, Robert Gagne defined learning as a ‘change in human disposition or capacity that persists over a period of time, and is not simply ascribable to processes of growth (1982: 2). In the 1990s learning was often described as the relatively permanent change in a person’s knowledge or behaviour due to experience:

{This] change may be deliberate or unintentional, for better or for worse. To qualify as learning, this change must be brought about by experience – by the interaction of a person with his or her environment. … the changes resulting from learning are in the individual’s knowledge or behaviour’ (Woolsfolk 1998: 204-205)

In these examples, learning is approached as an outcome – the product of some process. It can be recognized or seen. ‘Learning’, wrote De Hower et. al. (2013) is seen as a function that maps experience onto behaviour. In other words, here learning is defined as ‘an effect of experience on behaviour’

Viewing learning as a product, a thing, has the virtue of highlighting a crucial aspect of learning – change. Its apparent clarity may also make some sense when conducting experiments. However, it is a blunt instrument. For example:

- Does a person need to perform for learning to have happened?

- Are there other factors that may cause behaviour to change?

- Can the change involved include the potential for change? (Merriam and Caffarella 1991: 124)

Not all changes in behaviour resulting from experience involve learning, and not all changes in behaviours are down to experience. It would seem fair to expect that if we are to say that learning has taken place, experience could have been used in some way. For example, while conditioning may result in a behaviour change, the change may not involve drawing upon experience to generate new knowledge. Not surprisingly, many theorists have, thus, been less concerned with overt behaviour than with changes in how people ‘understand, or experience, or conceptualize the world around them’ (Ramsden 1992: 4) (see cognitivism below). The focus for them is gaining knowledge or ability using experience.

There have been attempts to redefine product or functional definitions of learning. For example, Domjan (2010: 17) discusses learning as an enduring change in the mechanisms of behaviour. De Houer et. al (2013) look at the adaptation of individual organisms to their environment during the lifetime of the individuals (after Skinner 1938).

Taxonomies

There have also been attempts to group outcomes. The best known of these is Benjamin S. Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives (1956) (Bloom chaired a group of members of the American Psychological Association (APA) exploring educational objectives – and edited the first volume of their work). The APA group identified three key areas or domains of educational objectives or learning:

- Cognitive: mental skills (knowledge).

- Affective: growth in feelings or emotional areas (attitude or self).

- Psychomotor: manual or physical skills (skills).

These domains (knowledge, attitudes and skills) have become part of the fabric of the field of education – both formal and informal. Each domain has then been split into different categories to analyse the nature of learning and to create a hierarchy of objectives.

Most attention, not surprisingly, has been given to the cognitive domain. A recent version of the taxonomy (Anderson et. al. 2001) had six categories – remember, understand, apply, analyse, evaluate, create. It then broke these down according to the type of knowledge involved: factual, conceptual, procedural, and metacognitive.

Attention was also paid to the affective domain in the second volume of the taxonomy (Kraftwohl et. al. 1964). Its categories were: receiving ideas; responding to ideas, phenomena; valuing ideas, materials; organization of ideas, values; characterisation by value set (or to act consistently in accordance with values internalised) (O’Neill and Murphy 2010). In this model, as O’Neill and Murphy comment, ‘The learner moves from being aware of what they are learning to a stage of having internalised the learning so that it plays a role in guiding their actions’.

The original taxonomy of the psychomotor domain has also been updated by Dave (1970). This mapping has several levels: perception /observing; guided response /imitation; mechanism; complex response; adaptation; and origination

Use of Blooms taxonomy faded during the late 1960s and 1970s but became a standard feature of practice again with the rise of national curriculums in places like the United Kingdom, and the concern with learning objectives and learnification that Biesta (2009) discusses (see above).

Gardeners or carpenters

The attraction of approaching learning as a product is that it provides us with something relatively clear to look for and measure. The danger is that it may not obvious what we are measuring – and that the infatuation with discrete learning objectives pushes people down a path that takes people away from the purpose and processes of education. It turns educators into ‘woodworkers’ rather than ‘gardeners’ (Gopnik 2016). As carpenters:

… essentially your job is to shape that material into a final product that will fit the scheme you had in mind to begin with. And you can assess how good a job you’ve done by looking at the finished product. Are the doors true? Are the chairs steady? Messiness and variability are a carpenter’s enemies; precision and control are her allies. Measure twice, cut once….

When we garden, on the other hand, we create a protected and nurturing space for plants to flourish. It takes hard labor and the sweat of our brows, with a lot of exhausted digging and wallowing in manure. And as any gardener knows, our specific plans are always thwarted…. And yet the compensation is that our greatest horticultural triumphs and joys also come when the garden escapes our control. (Gopnik 2016: 22)

Learning as a process

In Säljö’s categories two to five we see learning appearing as processes – memorizing, acquiring, making sense, and comprehending the world by reinterpreting knowledge. In his first category we find both process – acquiring – and product – a quantitative increase in knowledge. As might be expected, educationalists often look to process definitions of learning. They are interested in how activities interact to achieve different results. Similarly, researchers concerned with cognition are drawn to uncovering the ‘mental mechanisms’ that drive behaviour (Bechtel 2008).

Exploring learning as a process is attractive in many ways. It takes us to the ways we make sense of our thoughts, feelings and experiences, appreciate what might be going on for others, and understand the world in which we live. For us as educators, the attraction is obvious. The more we know about what activities are involved in ‘making sense’ and if, and how, they can be sequenced, the better we can help learners.

Given the role that ‘experience’ has in definitions of learning within psychology, it is not surprising that probably the most influential discussion of learning as a process is David Kolb’s exploration of experiential learning.

Kolb on experiential learning

Kolb (with Roger Fry) created his model out of four elements:

- concrete experience,

- observation and reflection,

- the formation of abstract concepts, and

- testing in new situations.

He represented these in the famous experiential learning circle that involves (1) concrete experience followed by (2) observation and experience followed by (3) forming abstract concepts followed by (4) testing in new situations (after Kurt Lewin).

Kolb and Fry (1975) argue that the learning cycle can begin at any one of the four points – and that it should really be approached as a continuous spiral.

There are a number of problems with this view of the learning process (see: https://infed.org/dir/david-a-kolb-on-experiential-learning/) but it does provide a helpful starting point for practitioners.

Kolb claims that he based his model on the work of Piaget, Lewin and Dewey. As Reijo Miettinen (2000) has shown it was a rather loose relationship. To approach learning as a process it is best to go back to Dewey – both because of his concern with experience, and his exploration of the nature of thinking/reflection. As a result we are going to look at:

- The nature of experience.

- Reflective thought.

- Making connections.

- Committing and acting (or rejecting and not acting).

Experience

So far, we have not looked at ‘experience’ in detail. It is a well-worn term often used with little attention to meaning. In the twentieth century it was, arguably, the work of John Dewey that did much to help rescue the notion – although even he gave up on it after a long struggle (Campbell 1995: 68). Experience, for him, was the ‘complex of all which it is distinctively human’ (Dewey 1929). It is ‘not a rigid and closed thing; it is vital, and hence growing’ (Dewey 1933) and stands at the centre of educational endeavour. The business of education, he wrote, ‘might be defined as an emancipation and enlargement of experience’ (1933: 340).

Dewey distinguished between two senses of the word: ‘having an experience’ and ‘knowing an experience’. The ‘having points to the immediacy of contact with the events of life; ‘knowing’ to the interpretation of the event (Boud et al 1993: 6). Sometimes experience can be seen just in the former sense – as a sensation. However, perhaps the most helpful way of viewing ‘experience’ is as an act of consciousness, an encounter with signals from the senses (see Gupta 2006: 223-236) for a discussion of experience as an act of consciousness).

Experience: Sometimes experience can be seen as a sensation. Perhaps the most helpful way of viewing it is as an act of consciousness, an encounter with signals from the senses.

Towards the end of his life, however, John Dewey regretted using the term ‘experience’ – partly because it was often misunderstood as an individual experience. He had long believed experience had a strong social dimension. In Experience and Nature, he argued:

Experience is already overlaid and saturated with the products of the reflection of past generations and by-gone ages. It is filled with interpretations, classifications, due to sophisticated thought, which have become incorporated (Dewey 1925: 40)

Subsequently, this concern with culture and the social nature of thinking became expressed in the work of influential educators such as Jerome Bruner (1996) and cognitive researchers interested in the ‘social brain’ (see Liberman 2013). Interestingly, cognitive researchers have generally held on to the idea of experience as part of the way of making sense of the process of learning while incorporating the social.

Reflective thinking

John Dewey took as his starting point practical, material life, activity. He saw non-reflective experience based on habits as a dominant form of experience. Reflection occurred when people sense or see a ‘forked road’ – contradictions or inadequacies in their habitual experience and ways of acting (Miettinen 2000).

Dewey defined reflective thought as ‘active, persistent, and careful consideration of any belief or supposed form of knowledge in the light of the grounds that support it and the further conclusions to which it tends’ (Dewey 1933: 118). He set out five phases or aspects.

- Suggestions, in which the mind leaps forward to a possible solution.

- An intellectualization of the difficulty or perplexity that has been felt (directly experienced) into a problem to be solved.

- The use of one suggestion after another as a leading idea, or hypothesis, to initiate and guide observation and other operations in collection of factual material.

- The mental elaboration of the idea, or supposition as an idea or supposition (reasoning, in the sense in which reasoning is a part, not the whole, of inference).

- Testing the hypothesis by overt, or imaginative action. (See Dewey 1933: 199-209) (For a discussion of these see Reflection, learning and education).

Later writers such as Boud, Keogh and Walker (1985) made emotions more central. For them reflection is an activity in which people ‘recapture their experience, think about it, mull it over and evaluate it’ (ibid: 19). They reworked Dewey’s five aspects into three.

- Returning to experience – that is to say recalling or detailing salient events.

- Attending to (or connecting with) feelings – this has two aspects: using helpful feelings and removing or containing obstructive ones.

- Evaluating experience – this involves re-examining experience in the light of one’s intent and existing knowledge etc. It also involves integrating this new knowledge into one’s conceptual framework. (ibid: 26-31)

This way of approaching reflection has the advantage of connecting with common modes of working e.g. we are often encouraged to attend to these domains in the process of supervision and journal writing. However, it is still a normative model, a process that the writers think should happen. It does not describe what may actually be happening when learning. For example, as Cinnamond and Zimpher (1990: 67) put it, ‘they constrain reflection by turning it into a mental activity that excludes both the behavioural element and dialogue with others involved in the situation’. Furthermore, do things happen in neat phases or steps?

Making connections

To be fair to John Dewey, he did appreciate that thinking may not proceed in nice, clear steps, and that the elements he identified in reflective thought are interconnected. As we have already seen, he talked about ‘suggestions, in which the mind leaps forward to a possible solution’. While Dewey talked of phases it is more helpful to think of these as processes that are, in effect, occurring concurrently. Nearly a hundred year later, thanks to advances in cognitive science, we have a better understanding of what might be going on.

It is becoming quite clear that the brain learns and changes as it learns. This process, called neuroplasticity or just plasticity, refers to the brain’s ability to rewire or expand its neural networks… New information enters the brain in the form of electrical impulses; these impulses form neural networks, connecting with other networks and the stronger and more numerous the networks the greater the learning. The brain learns when challenged. (Merriam and Bierema 2014: 171-2)

Alison Gopnik (2016) has highlighted the difference between children’s and adult’s brains around these processes.

Young brains are much more “plastic” than older brains; they make more new connections, and they’re much more flexible… A young brain makes many more links than an older one; there are many more possible connections, and the connections change more quickly and easily in the light of new experiences. But each of those links is relatively weak. Young brains can rearrange themselves effortlessly as new experiences pour in.

As we grow older, the brain connections that we use a lot become swifter and more efficient, and they cover longer distances. But connections that we don’t use get “pruned” and disappear. Older brains are much less flexible. Their structure has changed from meandering, narrow pathways to straight-ahead, long-distance information superhighways. As we get older our brains can still change, but they are more likely to change only under pressure, and with effort and attention. (Gopnik 2016: 31)

Young brains are designed to explore, to generate alternatives and to experiment. Older brains are designed to exploit – to move quickly to what works. We need both of course, but the danger is that we push children away from discovery learning and into making the ‘correct’ connections (what could be called mastery learning). A further problem is that in times of significant change these connections are difficult to undo – we need the ‘messiness’ of exploration and discovery. There is a basic tension between exploration and exploitation (Cohen et. al. 2007) and what John Dewey was attempting to do was to hold onto both.

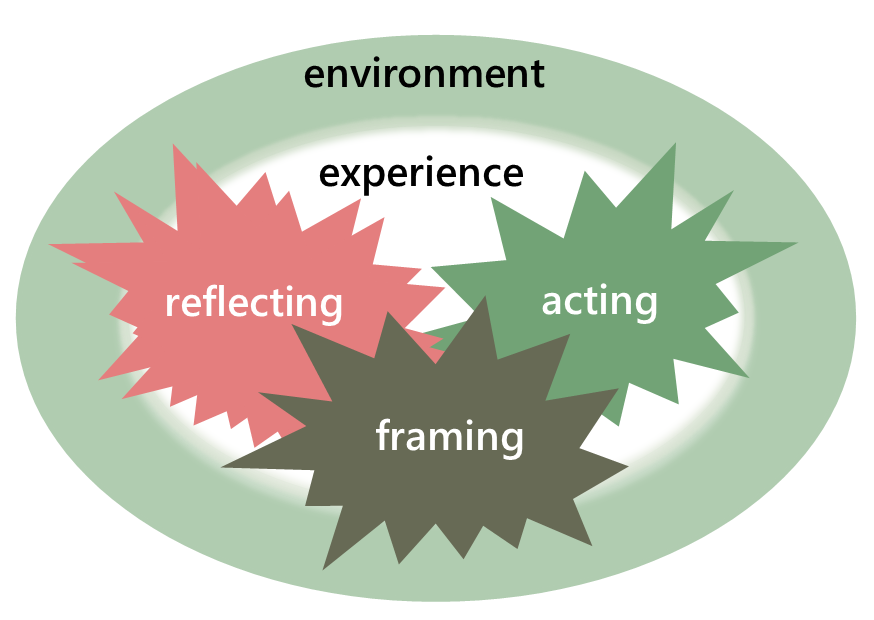

Framing and acting (or not acting)

One of the important aspects of the taxonomies of outcomes we explored earlier is that they take us beyond the cognitive domain (knowledge). To function well in the world, we must attend to the affective (attitudes and feelings), psychomotor (manual or physical skills), and relational. If learning is fully about change we have to connect reflection with acting – and with our mindset or frame of reference (what social pedagogues describe as haltung).

Also, once we have appreciated that experience cannot be approached without taking into account the social nature of learning, and of how our brains work, then it becomes clear that we need to look at what Aristotle described as the ‘practical’ (see what is praxis). We must frame our reflection and action.

Framing. As we have already seen, for John Dewey, thinking begins with a ‘forked-road’ – a question or situation that requires making choices. Within ‘practical’ orientation we must think about this situation in the light of our understanding of what is good or what makes for human flourishing. For Aristotle, this meant being guided by a moral disposition to act truly and rightly; a concern to further human well-being and the good life. This is what the ancient Greeks called phronesis and requires an understanding of other people. It also involves moving between the particular and the general.

The mark of a prudent man [is] to be able to deliberate rightly about what is good and what is advantageous for himself; not in particular respects, e.g. what is good for health or physical strength, but what is conducive to the good life generally. (Aristotle 2004: 209)

This process involves interpretation, understanding and application in ‘one unified process’ (Gadamer 1979: 275). It is something we engage in as human beings and it is directed at other human beings.

Acting. As can be seen from the diagram above, the outcome of the process of making judgements is a further process – interaction with others, tools etc. In traditional product definitions of learning this could be called behaviour. It might be that people decide not to change their behaviour or thinking – they carry on as they were. Alternatively, there could be a decision to change something. This might involve:

Planning. Classically this process involves developing pathways and strategies to meet goals; and deciding what might work best.

Trying out. Putting the plan into action.

Evaluating and try again. Here we go back to where we began – return to experience; reflect and building understandings; frame; and act. (Smith forthcoming)

I have brought these elements together in a simple diagram. The process of learning is inherently social. Our experiences and processes are ‘overlaid and saturated’ with ideas and feelings that are borne of interactions with others, and often takes place with others. We engage with experiences, reflect upon them, frame them (consciously or not), and act (or not). These processes are inevitably infused with the nature of the environment and experiences.

Elsewhere, we have explored the nature and process of pedagogy – and the orientation to action (see what is pedagogy?) In Aristotle’s terms pedagogy comprises a leading idea (eidos); what we are calling haltung or disposition (phronesis – a moral disposition to act truly and rightly); dialogue and learning (interaction) and action (praxis – informed, committed action) (Carr and Kemmis 1986; Grundy 1987). In the following summary, we can see where learning sits from the perspectice of the educator/pedagogue.

Consciousness of learning

One of the significant questions that arises is the extent to which people are conscious of what is going on. Are they aware that they are engaged in learning – and what significance does it have if they are? Such questions have appeared in various guises over the years – and have surfaced, for example, in debates around the rather confusing notion of ‘informal learning‘.

One particularly helpful way of approaching the area has been formulated by Alan Rogers (2003). Drawing especially on the work of those who study the learning of language (for example, Krashen 1982), Rogers sets out two contrasting approaches: task-conscious or acquisition learning and learning-conscious or formalized learning.

Task-conscious or acquisition learning. Acquisition learning is seen as going on all the time. It is ‘concrete, immediate and confined to a specific activity; it is not concerned with general principles’ (Rogers 2003: 18). Examples include much of the learning involved in parenting or with running a home. Some have referred to this kind of learning as unconscious or implicit. Rogers (2003: 21), however, suggests that it might be better to speak of it as having a consciousness of the task. In other words, whilst the learner may not be conscious of learning, they are usually aware of the specific task in hand.

Learning-conscious or formalized learning. Formalized learning arises from the process of facilitating learning. It is ‘educative learning’ rather than the accumulation of experience. To this extent there is a consciousness of learning – people are aware that the task they are engaged in entails learning. ‘Learning itself is the task. What formalized learning does is to make learning more conscious to enhance it’ (Rogers 2003: 27). It involves guided episodes of learning.

When approached in this way it becomes clear that these contrasting ways of learning can appear in the same context. Both are present in schools. Both are present in families. It is possible to think of the mix of acquisition and formalized learning as forming a continuum.

At one extreme lie those unintentional and usually accidental learning events which occur continuously as we walk through life. Next comes incidental learning – unconscious learning through acquisition methods which occurs during some other activity… Then there are various activities in which we are somewhat more conscious of learning, experiential activities arising from immediate life-related concerns, though even here the focus is still on the task… Then come more purposeful activities – occasions where we set out to learn something in a more systematic way, using whatever comes to hand for that purpose, but often deliberately disregarding engagement with teachers and formal institutions of learning… Further along the continuum lie the self-directed learning projects on which there is so much literature… More formalized and generalized (and consequently less contextualized) forms of learning are the distance and open education programmes, where some elements of acquisition learning are often built into the designed learning programme. Towards the further extreme lie more formalized learning programmes of highly decontextualized learning, using material common to all the learners without paying any regard to their individual preferences, agendas or needs. There are of course no clear boundaries between each of these categories. (Rogers 2003: 41-2)

This distinction is echoed in different ways in the writings of many educationalists – but in particular in key theorists such as Kurt Lewin, Chris Argyris, Donald Schön, or Michael Polanyi.

Learning theory

The focus on process obviously takes us into the realm of learning theories – ideas about how or why change occurs. On these pages we focus on five different orientations (taken from Merriam, Caffarella, & Baumgartner 2007).

- The behaviourist orientation to learning

- The cognitive orientation to learning

- The humanistic orientation to learning

- The social/situational orientation to learning

- The constructivist/social constructivist orientation to learning

As with any categorization of this sort the divisions are a bit arbitrary: there could be further additions and sub-divisions to the scheme, and there are various ways in which the orientations overlap and draw upon each other.

The five orientations can be summed up in the following figure:

Five orientations to learning (after Merriam and Bierema 2012)

| Aspect | Behaviourism | Cognitivism | Humanism | Social cognitive theory | Constructivism |

| Learning theorists | Thorndike, Pavlov, Watson, Guthrie, Hull, Tolman, Skinner | Koffka, Kohler, Lewin, Piaget, Ausubel, Gagne | Maslow, Rogers | Bandura, Rotter | Bruner, Dewey, Lave and Wenger, and Vygotsky |

| View of the learning process | Change in behaviour | Internal mental process (including insight, information processing, memory, perception | A personal act to fulfil potential. | Interaction with and observation of others in a social context | Learning is creating meaning from experience |

| Locus of learning | Stimuli in external environment | Internal cognitive structuring | Affective and cognitive needs | Learning is in relationship between people and environment. | Individual and social construction of knowledge / understanding |

| Purpose in education | Produce behavioural change in desired direction | Develop capacity and skills to learn better | Become self-actualized + autonomous | To learn new roles + behaviors | To build understanding and knowledge |

| Educator role | Arranges environment to elicit desired response | Structures content of learning activity | Facilitates development of the whole person | Model and facilitate new roles and behaviours | Works to help build settings in which conversation + participation can occur. |

| Manifest-ations in adult learning | Behavioural objectives Competency -based education. Skill development and training |

Cognitive development Intelligence, learning and memory as function of ageLearning how to learn |

Andragogy Self-directed learning |

Socialization

Self-directed learning Mentoring |

Experiential learning

Transforma- tional learning Reflective practice Communities of practice |

As can seen from the above schematic presentation and the discussion on the linked pages, these approaches involve contrasting ideas as to the purpose and process of learning and education – and the role that educators may take. It is also important to recognize that the theories may apply to different sectors of the acquisition-formalized learning continuum outlined above. For example, the work of Lave and Wenger is broadly a form of acquisition learning that can involve some more formal interludes.

Further reading

Gopnik, A. (2016). The Carpenter and the Gardener. What the New Science of Child Development Tells Us about the Relationship Between Parents and Children. London: Boadley Head. This is an excellent critique of the contemporary concern with ‘parenting’ and provides an accessible overview of recent research into the ways children learn from each other, and adults.

Lieberman, M. D. (2013). Social. Why Our Brains Are Wired to Connect. Oxford: Oxford University Press. A good introduction to the development of thinking around the social brain. It includes some discussion of the relevance for educators.

Merriam, S. B., Caffarella, R. S., & Baumgartner, L. M. (2012). Learning in adulthood: a comprehensive guide. 3e. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Pretty much the standard text for those concerned with adult education and lifelong learning. It is, as it states in the title, a comprehensive guide.

References

Anderson, L. W., Krathwohl, D. R., & Bloom, B. S. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of educational objectives. New York: Longman.

Aristotle (2004). The Nicomachean Ethics. Trans. J. A. K. Thomson. London: Penguin.

Bates, B. (2016). Learning Theories Simplified …and how to apply them to teaching. London: Sage.

Bechtel, W. (2008). Mental mechanisms: Philosophical perspectives on cognitive neuroscience. London: Routledge.

Biesta, G. J. J. (2009). Good education in an age of measurement: on the need to reconnect with the question of purpose in education. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability 21(1), 33–46.

Biesta, G. J. J. (2018) ‘Interrupting the politics of learning’ in K. Illeris (ed). (2018). Contemporary Theories of Learning: Learning Theorists … In Their Own Words. Abingdon: Routledge.

Bloom, B. S., Engelhart, M. D., Furst, E. J., Hill, W. H., and Krathwohl, D. R. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. New York: New York.

Boden, M. A. (1979). Piaget. London: Fontana.

Boud. D. and Miller, N. (eds.) (1997). Working with Experience: animating learning. London: Routledge.

Bruner, J. S. (1960, 1977). The Process of Education, Cambridge Ma.: Harvard University Press.

Bruner, J. S. (1966). Toward a Theory of Instruction, Cambridge, Mass.: Belkapp Press.

Bruner, J. S. (1971). The Relevance of Education, New York: Norton.

Bruner, J. S. (1973). Going Beyond the Information Given. New York: Norton.

Bruner, J. S. (1996). The Culture of Education. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Carr, W. and Kemmis, S. (1986). Becoming Critical. Education, knowledge and action research. Lewes: Falmer.

Cinnamond, J. H. and Zimpher, N. L. (1990). ‘Reflectivity as a function of community’ in R. T. Clift, W. R. Houston and M. C. Pugach (eds.) Encouraging Reflective Practice in Education. An analysis of issues and programs. New York: Teachers College Press.

Cohen, J. D., McClure, S. M., and Yu, A. J. (2007). “Should I Stay or Should I Go? How the Human Brain Manages the Trade-off Between Exploitation and Exploration.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 362, no. 1481933–42. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2007.2098.

Dave, R. H. (1970). Psychomotor Levels in Armstrong, R. (ed.) Developing and Writing Behavioral Objectives.Tucson AZ: Educational Innovators Press.

De Houwer, J., Barnes-Holmes, D. and Moors, A. (2013). What is learning? On the nature and merits of a functional definition of learning, Psychon Bull Rev.

DOI 10.3758/s13423-013-0386-3. [https://ppw.kuleuven.be/okp/_pdf/DeHouwer2013WILOT.pdf. Retrieved June 8, 2018].

Dewey, J. (1915) The School and Society, 2e., Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Dewey, J. (1925, 1988). Experience and nature. The Later Works of John Dewey Vol. 1. Edited by Jo Ann Boydston. Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press).

Dewey, J. (1933). How We Think 2e. New York: D. C. Heath.

Dewey, J. (1934). Art as Experience. New York: Perigee Books.

Dewey, J. (1939). Education and Experience. New York: Collier Books.

Domjan, M. (2010). Principles of learning and behaviour. 6e. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Cengage.

Fink, L. D. (2003). Creating significant learning experiences: An integrated approach to designing college courses. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Freire, P. (1972) Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Freire, P. and Faundez, A. (1989) Learning to Question. A pedagogy of liberation, Geneva: World Council of Churches.

Gagné, R. M. (1985) The Conditions of Learning 4e, New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Gopnip, A. (2016). The Carpenter and the Gardener. What the New Science of Child Development Tells Us about the Relationship Between Parents and Children. London: Boadley Head.

Gravett, S. (2001). Adult learning. Pretoria, SA: Van Schaik Publishers.

Gruber, H. E. and Voneche, J. J. (1995). The Essential Piaget: an interpretative reference and guide. London: Northvale.

Grundy, S. (1987). Curriculum: Product or praxis. Lewes: Falmer.

Gupta, A. (2006). Empiricism and Experience. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hartley, J. (1998) Learning and Studying. A research perspective. London: Routledge.

Hergenhahn, B. R. and Olson, M. H. (1997). An Introduction to Theories of Learning 5e. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Illeris, K. (2002). The Three Dimensions of Learning. Contemporary learning theory in the tension field between the cognitive, the emotional and the social, Frederiksberg: Roskilde University Press.

Illeris, K. (2016). How We Learn: Learning and non-learning in school and beyond. Abingdon: Taylor and Francis.

Illeris, K. (ed). (2018). Contemporary Theories of Learning: Learning Theorists … In Their Own Words. Abingdon: Routledge.

Joyce, B., Calhoun, E. and Hopkins, D. (1997). Models of Learning – tools for teaching. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Jarvis, P. (1987). Adult Learning in the Social Context. London: Routledge.

Kelly, L. (2002). What is learning … and why do museums need to do something about it? A paper presented at the Why Learning? Seminar, Australian Museum/University of Technology Sydney, 22 November. [https://australianmuseum.net.au/uploads/documents/9293/what%20is%20learning.pdf. Retrieved June 7, 2018].

Kirschenbaum, H. and Henderson, V. L. (eds.) (1990). The Carl Rogers Reader. London: Constable.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential Learning. Englewood Cliffs, NJ.: Prentice Hall.

Krathwohl, D.R., Bloom, B.S., and Masia, B.B. (1964). Taxonomy of educational objectives: Handbook II: Affective domain. New York: David McKay Co..

Krashen, S. D. (1982). Principles and Practice in Second Language Acquisition. Oxford: Pergamon.

Lave, J. and Wenger, E. (1991). Situated Learning. Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press.

Leach, J. and Moon, B. (eds.) (1999). Learners and Pedagogy. London: Paul Chapman.

Lieberman, M. D. (2013). Social. Why Our Brains Are Wired to Connect. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Maslow, A. (1968). Towards a Psychology of Being 2e. New York: Van Nostrand.

Maslow, A. (1970). Motivation and Personality 2e. New York: Harper and Row.

McCormick, R. and Paetcher, C. (eds.) (1999). Learning and Knowledge. London: Paul Chapman.

Mellanby, J. and Theobald, K. (2014). Education and Learning: An Evidence-based Approach. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell.

Merriam, S. B. (2008). Third Update on Adult Learning Theory: New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, Number 119 (J-B ACE Single Issue Adult & Continuing Education). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Merriam, S., and Bierema, Laura L. (2014). Adult learning: Linking theory and practice. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Merriam, S. B. and Caffarella (1991, 1998). Learning in Adulthood. A comprehensive guide. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Merriam, S. B., Caffarella, R. S., & Baumgartner, L. M. (2012). Learning in adulthood: a comprehensive guide. 3e. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com

Mezirow, J. (1991). Transformative Dimensions of Learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Miettinen, R. (2000). The concept of experiential learning and John Dewey’s theory of reflective thought and action, International Journal of Lifelong Education, 19:1, 54-72, DOI: 10.1080/026013700293458. [https://doi.org/10.1080/026013700293458. Retrieved: June8, 2018].

Murphy, P. (ed.) (1999). Learners, Learning and Assessment. London: Paul Chapman.

Newman, F. and Holzman, L. (1997). The End of Knowing. A new developmental way of learning. London: Routledge.

O’Neill, G. and Murphy, F. (2010). Assessment. Guides to taxonomies of learning. Dublin: University College Dublin. [http://www.ucd.ie/t4cms/ucdtla0034.pdf. Retrieved: June 10, 2018].

Piaget, J. (1926). The Child’s Conception of the World. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Piaget, J. (1953). The Origin of Intelligence in Children. New York: International Universities Press.

Ramsden, P. (1992). Learning to Teach in Higher Education. London: Routledge.

Rogers, A. (2003). What is the Difference? A new critique of adult learning and teaching. Leicester: NIACE.

Rogers, C. and Freiberg, H. J. (1993) Freedom to Learn (3rd edn.), New York: Merrill.

Ryle, G. (1949, 1990) The Concept of the Mind. London: Penguin Books.

Säljö, R. (1979). ‘Learning in the learner’s perspective. I. Some common-sense conceptions’, Reports from the Institute of Education, University of Gothenburg, 76.

Salomon, G. (ed.). Distributed Cognitions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Salzberger-Wittenberg, I., Henry, G. and Osborne, E. (1983). The Emotional Experience of Learning and Teaching. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Skinner, B. F. (1938). The behavior of organisms: An experimental analysis. New York: Appleton-Century.

Skinner, B. F. (1973). Beyond Freedom and Dignity. London: Penguin.

Smith, M. K. (1994). Local Education. Community, conversation, action. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Smith, M. K. (forthcoming). Working with young people in difficult times. Offering sanctuary, community and hope.

Tennant, M. (1988, 1997). Psychology and Adult Learning. London: Routledge.

Tennant, M. and Pogson, P. (1995). Learning and Change in the Adult Years. A developmental perspective. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Retallick, J., Cocklin, B. and Coombe, K. (1998). Learning Communities in Education. London: Cassell.

Wenger, E. (1999) Communities of Practice. Learning, meaning and identity, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Witkin, H. and Goodenough, D. (1981). Cognitive Styles, Essence and Origins: Field dependence and field independence. New York: International Universities Press.

Woolsfolk, A. 1998). Educational Psychology. 7e. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Zull, J. E. (2006). Key aspects of how the brain learns. In S. Johnson & K. Taylor (Eds.), The neuroscience of adult learning (pp. 3–10). New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, No. 110, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Links

Explorations in Learning & Instruction: The Theory Into Practice Database – TIP is a tool intended to make learning and instructional theory more accessible to educators. The database contains brief summaries of 50 major theories of learning and instruction. These theories can also be accessed by learning domains and concepts.

University of Southampton What do the learning theories say about how we learn? https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/learning-network-age/0/steps/24637

https://study.com/academy/lesson/learning-theory-in-the-classroom-application-trends.html

How to cite this article: Smith, M. K. (1999-2020). ‘Learning theory’, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/dir/learning-theory-models-product-and-process/. Retrieved: insert date].

© Mark K. Smith 1999, 2003, 2018, 2020

updated: August 9, 2025